Mary Cassatt, Automne, portrait de Lydia Cassatt

Gardens brought indoors

This month of May has been more like March, with constant gusts of wind and rain, so visiting the museum at Giverny today was a tonic. Gardens brought indoors! On top of that, it was exciting to venture out to Normandy after a long, long winter of confinement, to visit beautiful villages like Vetheuil, where Joan Mitchell lived. But also Fourges, with its beautiful restaurant and mill, and La Roche-Guyon, with its castle affixed to the chalk cliffs.

And at Giverny, the rain even stopped long enough for us to eat in the patio of Baudy, which used to be the hotel painters would stay in.

Once inside the museum, the expressive painting by Mary Cassatt struck me. The complementary colors of fall, the vivid brushwork, but not only. The pallor of her sister lost in thought presages her death soon after, and the mood is distinct from many of Cassatt’s scenes of women and children.

And then there are more uplifting paintings like Jardin en Fleurs, full of light and color, painted with the exacting hand of young Monet.

Monet, Jardin en Fleurs, 1866

Whom we see evolve towards more abstract paintings that are so iconic.

Installation view

Joan Mitchell’s monumental, immersive symphony of color shows so much similarity to later Monet. It is probably not serendipitous that she lived near Giverny for some time!

Joan Mitchell, La Grande Vallée IX

There were many pieces by Bonnard, and here we can enjoy his graphic patterns and colors.

Bonnard, La Seine à Vernon, 1915

But the most surprising painting to me was this study by Vuillard, with its delicate layering of glazes, sketch-like quality with loose brushwork, intimate feel, and near obliteration of figurative elements like the table and figure in the background. In an exhibition full of color, this was different. Restrained yet unrestrained, it brought me in. Unfortunately the vividness is lost in the photo, which goes to show—you have to see it in person!

Edouard Vuillard, La Divette, Cabourg.

Authenticity in Art

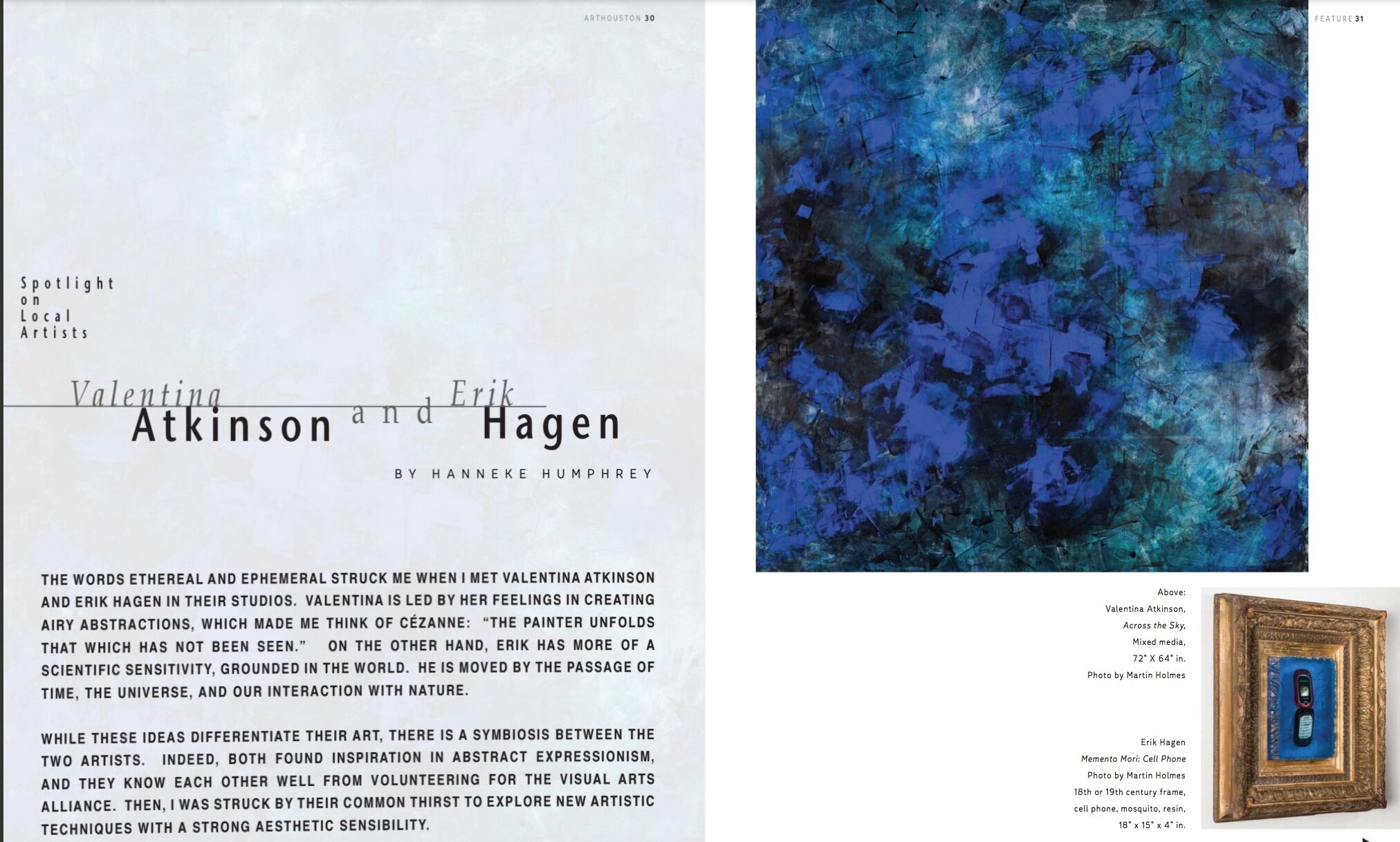

It was wonderful to reconnect with these Houston-based artists and write for Art Houston.

Here’s the link:

https://issuu.com/johnbernhard/docs/arthouston_magazine__12

Marmottan

Marmottan isn’t just any museum—it’s a stroll back in time to the Belle Époque. Just entering, you land in that luscious dining room with lovely paintings by Berthe Morisot adorning it. She was there and elsewhere, in galleries dedicated just to her upstairs.

Last visiting just before the second lockdown, I was counting the days to go back this month. But it is now clear that even more patience is needed. For Marmottan has a magnetic quality that beckons you to return. It is welcoming, even cozy, just as a home, and replete with treasures. Mansions are not always intimate, but this one is. And it is a warm change from the the more regal museums in the city. I would wager that even the most recalcitrant of visitors wouldn’t resist its charm.

While sidetracked by everything on view, we had actually come to see Cezanne and the Dreams of Italy exhibition. Much has been written, and criticized, on how the curators juxtaposed his paintings with those of Italian masters to whom he looked for inspiration. The comparisons did seem far fetched sometimes. Yet what struck me was the force, the determination of this sullen, restless personality relentlessly seeking his own path. Impressionism, with its ephemerality, was not for him, while the Old Masters offered concrete solidity that was satisfying.

I could sense the grueling journey. The early paintings are writhing and dark, as the Strangled Woman or The Murder below. Definitely not a happy camper, Cezanne.

Cezanne, La Femme Etranglee

Cezanne, Le Meurtre, c 1870

Eventually he broke new ground, as we know with the iconic St Victoire and other work. I discovered Seated Man below, a dignified, confident, and, yes, solid, portrait. His hand and feet seem almost sculpted, securely implanted, at one with nature. As Cezanne established his signature style, with planes of color, light infused his paintings, and what glowing light it is.

Homme Assis, 1905-6

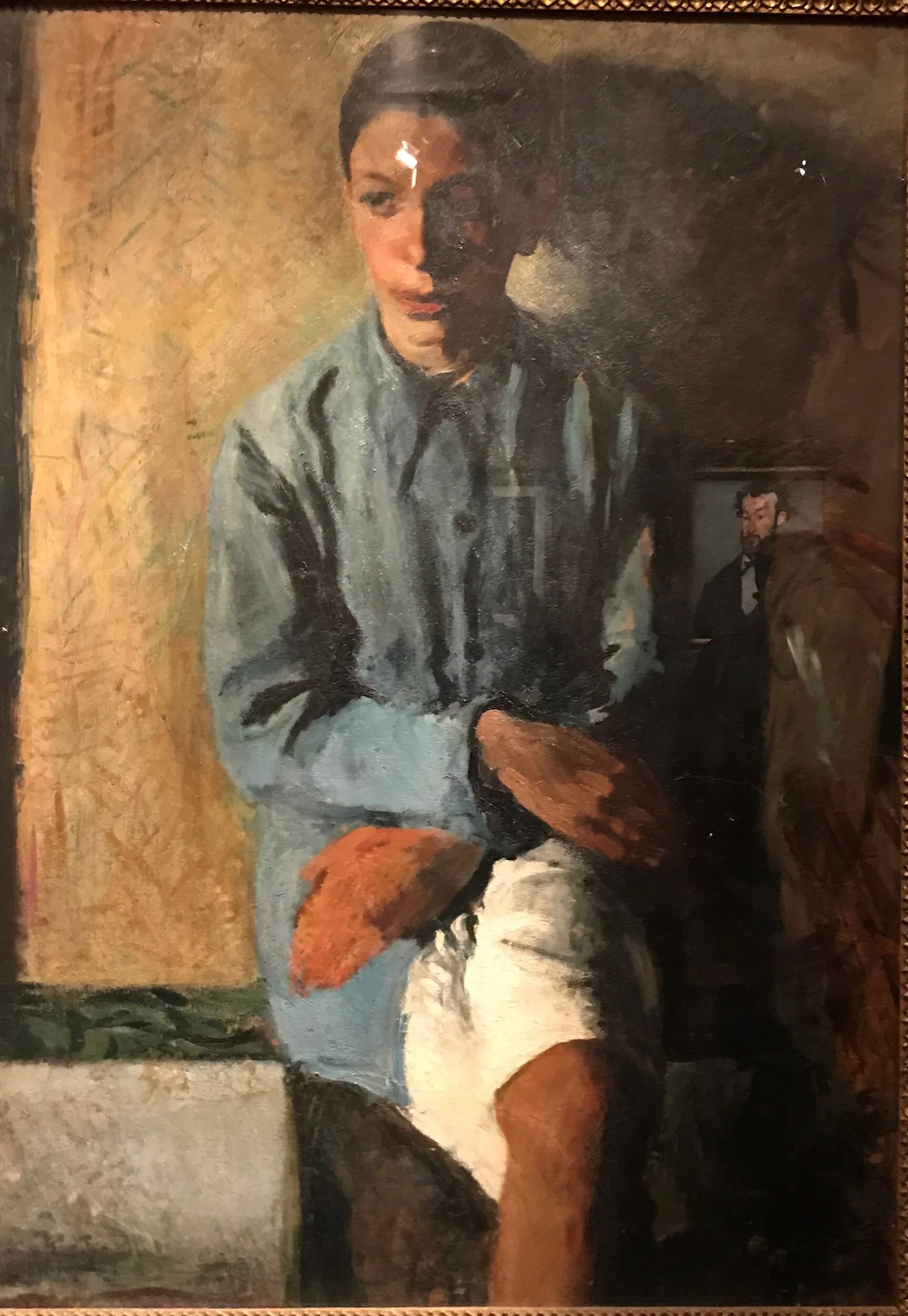

A jewel of this exhibition was its full-circling towards 20th century Italian artists in turn influenced by Cezanne. Morandi, Boccioni, Pirandello, and other artists not often present in exhibitions. Mario Sironi was one of my favorites, with such a warm palette and expressivity. Do you see similarities with Cezanne in this boy?

Portrait du frère Hector, Sironi

Sironi, Autoportrait, 1909

Finally, it was a special joy to be face-to-face with paintings by Morandi, and not just the meditative, minimalist still lives for which he is so known. The graphic simplicity and muted palette of this landscape emanate peacefulness, just as the still lives that he revisited over and over again in his Bologna studio. Their restful mood is the perfect ending to this wonderful exhibition.

Morandi, Paysage, 1942

Morandi and Cezanne installation

Opulence and the Haukohl Collection

Published Article in Art Houston

I had the opportunity to sit down with Sir Mark Fehrs and discover his impressive collection. Here is a link to the article I wrote in Art Houston.

American Explorations

Étude, Theodore Robinson

Giverny is always an uplifting immersion in resplendent nature and art, and the current exhibition is also the perfect place for an American like me to learn about, well, American art. Studio of Nature showcases plein air landscapes from 1860 to 1910, but what makes the show really exciting is discovering lesser known artists and their curiosity. They were intrigued by bubbling innovations in Europe as well as the grandiose vistas of their own country.

L’Iceberg, Frederic Edwin Church

Starting with Hudson River artists like Frederic Edwin Church, the majesty of the American landscape with dramatic realism leads the way.

Then the ambiance shifts to the moody melodies of Whistler. With his Nocturnes and Variations, this trailblazer broke away from realism towards minimalistic meditations as in the aqueous, atmospheric paintings and etchings here.

Nocturne, Palais, Whistler

Nocturne, Whistler

Variations en Violet et Vert, Whistler

And then, the wonderfully eclectic William Merritt Chase. A huge influence as a teacher (his school is now Parsons), he was such a prolific and exploratory artist. Untitled hints to Whistler, whom Chase had met, whereas the Olive Orchard bathes in sunlight, and Shinnecock is graphic and linear.

Chase, as many of his contemporaries, studied and worked in Europe, especially lured towards Paris, the artistic capital. Many attended the Royal Academy of Munich and the Académie Julian, and from there often headed to Monet’s fief.

Untitled, William Merritt Chase

L’Oliveraie, Chase

Matin sur la Digue Shinnecock, Chase

Arbres en Fleur, Theodore Robinson

Hence American Impressionism bloomed, and a group called The Ten pretty much mimicked the French Impressionists in splitting from the Salons.

A delightful discovery for me was Theodore Robinson with his dazzling and fresh Etude. Or his daring Arbres en Fleur, its plunging perspective, and near abstraction. The figures in symbiosis with nature are beguiling. Having a weak constitution due to asthma, you can just imagine him cooped up inside the Hotel Baudy, maybe taking a photograph of this scene.

Le Bassin de Nénuphars, Willard Metcalf

The list of artists goes on: Childe Hassam, sometimes called the American Impressionist, John Henry Twachtman, one of the most inventive painters of that generation, and Willard Metcalf, the first American painter who spent time in Giverny. His lilies are delectable.

L’Apres Midi D’Automne, Lilla Cabot Perry

And then there’s Lilla Cabot Perry. Have you heard of her? She became a close friend of Monet, quite a feat as he was tired of the American invasion in his town. Speaking French likely helped. And she was indeed highly cultivated, from old New England stock to boot, championing artists like Monet in the US. But she was a largely self-taught painter, only taking lessons in her 30s. Perhaps history doesn’t repeat, but stories of women do rhyme.

All of this allowed me to embrace the thirst of American artists who travelled far, soaked up new ideas, and came back to the US reinvigorated. To me, that’s the source of enrichment and innovation.

Opening Museum Doors Wide

Access tour, MFAH

I’m such a fan of making museums welcoming for everyone, of moving away from austere temples, the ones that my kids became turned off by and, well, aren’t necessarily running back to. Getting them to love these spaces as much as me was definitely not one of my motherly successes. Or of museums. As marketers say, it’s immensely more profitable to retain customers than to attract new ones.

Creating a space that people want to experience and come back to naturally means targeting not just young people but all reference groups. And Access Tours, for those with memory, hearing, or sight difficulties, have been one of my highlights in art education. I love the enthusiasm of these visitors who are deeply appreciative to be in this beautiful space, especially when it is reserved just for them. A precious moment. Proof of the pudding is seeing the same faces time and again who mark the date on their monthly calendars. And they are not just excited about seeing art, but the whole experience is what brings them back—discovering, listening, discussing, being together.

So, you might ask, what did we talk about? Well on the agenda was the male and female gaze in 19th century Impressionistic France—Auguste Rodin’s raw sculpture in stark contrast to Berthe Morisot’s delicate paintings.

The Crouching Woman, stock photo

Gallery view, MFAH

The Crouching Woman, with a nude woman in a terribly uncomfortable position is an enigma. It is mind-boggling how a model could have held that pose. I’ve tried it, with no success. Why would Rodin be interested in that torturous position? But then, what about her? What is she doing and thinking, peering downward, perhaps sadly, perhaps modestly, as she is attempting to cover herself?

The movement and contrasts are mesmerizing. Despite her awkward perch on an unstable rock, she somehow looks balanced. Even strong and unbreakable. While some parts of the sculpture are glistening, others are rough, unfinished. The light shimmers on the bronze sculpture’s myriad of lines.

Jeune Femme

The Basket Chair

Then Berthe Morisot, one of my favorite artists whom I have a hard time not boring everyone with. We talked about the evolution from realism in Jeune Femme to her signature Impressionist style in The Basket Chair. About being a female artist in a man’s world. About being constrained to domestic scenes. About not being more renowned. About the beseeching, melancholic expressions of her models, despite their privileged status. About her lovely, dashing brushwork and iridescent colors. How different from Rodin’s depictions of women. And how animated the conversation!

Access tour

My dear father would have loved this experience, which fosters community and engagement. And not only my father, but my mom too. Part of the brilliance of these tours is how they also create an outlet for those caring for their loved ones. Enjoyment, stimulation, support outside of the 24/7 responsibility.

Can’t wait for the doors to open again for one of the most edifying programs that I’ve known.

All photos my own except The Crouching Woman stock

Lina, oil, 8x10

Learning is a learning experience

It’s no news that virtual meetings and online galleries have become the new norm. And with that, I have been astounded by online learning, such as Moma’s myriad of classes with a treasure chest of resources. But a vehicle that would never have come to mind is painting classes.

Isn’t the physical experience so primordial to learning to paint? Well, I was proven wrong. Once lockdown set in, some teachers and schools were nimble in making the switch, and I signed onto the adventure. What I found out is that not only did it prod instructors out of their comfort zone, to dispense their classes in novel and interesting ways, but it also made me more attentive. Without the social aspect, there are fewer distractions, and I actually soak up a bit more.

Study of Zorn’s Cigarette Girl

Of course I will relish the day that we can join together again. But classes with Michael Downs in Calgary have especially energized me. The funny part is that we have never physically met and were introduced by a dear friend! His investment is tremendous, from organizing 4 short sessions a week, with diverse paint-alongs, critiques, and talks. All of a sudden, I’m not laboring forever on pieces that become overworked and boring, but speeding up and moving on. They’re certainly not masterpieces, but what’s more important is that the process makes me happy. I sure hope that he continues online once distancing passes.

The pictures you see come out of that process. Michael introduced me to Zorn’s limited palette of 4 colors, with a quick value-driven block in. From that, I practiced on my own with the resultant Lina, a political figure here in Houston.

Forward!

Here’s more on Michael:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Art-School/Michael-J-Downs-Open-Studio-2057790144435948/

#michaeljdowns. #portrait #portraitpainting #portraits

Oasis of Splendor

Silver Palm from the Mosaic series

Silvia Pinto Souza and I were supposed to organize a show of her work in April, but of course we know what happened with that! I’m hoping to see her work up soon, as it is fresh and uplifting. Just what we need right now.

“Art should be an oasis: a place or refuge from the hardness of life.” Fernando Botero’s quote comes to mind when gazing at Silvia’s paintings. She uplifts ordinary objects with verdant paintings, creating art that soothes even in complicated times. She finds splendor in the natural world, delighting in the delicate shapes and striking hues of flowers and fruits. Reminiscent of her roots in South America, her palette is rich and vivid, with subtle textures.

Her body of work consists of diverse series, including Mosaic Paintings, Florals, and Still Lives. She paints to the senses, to what speaks to her heart. A beautiful image is what she wants, and as she says ‘The true objective in Art is the pursuit of happiness, but the world seems to have forgotten about it.’

Silver Palm from the Mosaic series straddles between abstraction and representation, appearing as fragmented, pixelized images up close, but developing a reverberating harmony from a distance. Silvia’s inspiration stems from her experience with photo-montage and abstract geometrical work, but also from the ancient tradition of laying tiles. Working square by square on a canvas, each square becomes a painting in itself.

Red Pot

Her Florals and Still Lives dazzle, taking recognizable objects as a basis for painterly exploration. As Red Pot, one takes refuge in the beauty of saturated color and vibrant shapes. By flattening perspective, the focus on the flowers is amplified.

Another quote of hers resonates with me during these troubled times: “Man needs music, literature, and painting-all those oases of perfection that make up art-to compensate for the rudeness and materialism of life."

Silvia’s professional background started with Architectural Draftsmanship, followed by an Arts diploma from the Byam Shaw School of Art and Design (now part of the University of the Arts London), and a photoprinting class at the Slade School of Art. While living in Rio de Janeiro, she worked with printing techniques at the Pontificia Universidade Catolica and the Parque Lage Art Center. For her last 25 years in Houston, she has focused solely on painting. She is an exhibiting artist member of the Archway Gallery in Houston, and her works are displayed in private collections in various countries.

Her website: www.sps-art.com

Rusinol Prats, Valle de los Naranjos

Crossroads generation of Spain

Sorolla, After the Bath

Sorolla is always inspiring to me, with all his bravoura and mastery of every key of painting. Maybe not the most contemporary painter you might say, but studying a master as him goes far in helping a student as me. Just look at all the natural and reflected light here—isn’t it gorgeous?

He and his generation of Spanish painters are not the most top of mind either, something which always intrigued me. And maybe that is because art critics of the 20th c put them on the wayside, instead applauding the avant garde, the abstract. Duchamp and company were heralded in, and Sorolla and company a bit forgotten. He had stuck to his guns, championing a naturalistic, color-filled style that was his hallmark. But he was also sandwiched between greats like Goya and Picasso. They, and the troubled times of the fallen Spanish Empire, cast a shadow over artists like Sorolla.

And he was not the only turn-of-the-century artist forgotten. Who has heard of Rusinol Prats, Casas y Carbo, Nunell, Anglada Camarasa? Many of you, but not me until recently. They were all part of the Barcelona avant garde, hanging out in the iconic tavern Père Rameu, championing the renewal of Spanish culture. And they spent lots of time in Paris, the center of modern art, imbibed in the cultural scene there, friends with the artistic leaders. What’s especially appealing is that these artists were all inspired by the French but maintained their own Hispanidad.

Rusinol Prats, Calvario at Sajunto

I especially love Rusinol Prats and Casas y Carbo, who were like blood brothers, inseparable, and leaders of the Père Rameu scene. Rusinol’s landscapes are either moody, as in « Calvario at Sajunto », with the cypresses representing as he said tombstones of the poor. Or they would be glorious, redundant with color, as in « Valle de los Naranjos ». The magnificent warm light of Catalonia bathes the scene, a similar light to that of Sorolla.

Casas y Carbo, Le Moulin de la Galette

Casas y Carbo, La Sagartain

Casas y Carbo’s portraits are particularly modern to me, with « Le Moulin de la Galette » depicting a woman enjoying some of the vices usually reserved to men. Ah, that mysterious gaze. And « La Sagartain », his mistress enveloped in that resplendent yellow with an altogether different gaze. Not a woman to be toyed with.

I first discovered these artists at the Orangerie in 2012, an exhibition called « L’Espagne Entre Deux Siècles Zuloaga à Picasso ». The piece on the cover by Anglada Camarasas is in itself a showstopper. Avant garde with a little bit of Klimt?

https://www.boutiquesdemusees.fr/en/exhibition-catalogues/exhibition-catalogue-lespagne-entre-deux-siecles-de-zuloaga-a-picasso/2882.html

WORSE THINGS HAPPEN AT SEA: CECILY BROWN'S MADREPORA (SHIPWRECK), 2016. OIL ON LINEN, 97 X 151 1/8 INCHES. PHOTO: COURTESY OF PAULA COOPER

Indulge with Cecily Brown

At a time when the term is an elephant in the room, could Cecily Brown’s art be referred to as Romantic? Cecily feeds into my nostalgia with luscious paint, singing color, curving forms. Not sharp and edgy. As with Kandinsky, her unrestrained, abstract shapes and brilliant colors suggest emotional expression. They also have the romantic exuberance of abstract expressionism. With a dose of ambiguity, mystery. The gorgeousness of her work beguiles me in, and I slowly discover figures and narratives in these abstract forms.

She was brought up in England, her mother a writer, her father an art critic and curator. She herself went to the Slade School and embraced painting. Real, gestural painting with a brush. At a time when the fashion was all but that. The YBAs like Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin were the rage, and Cecily was a bit of a fish out of water. She quickly moved to NYC, maybe more accepting of her brand of art, and has stayed.

She loves the Old Masters, Bruegel, Bosch, and newer ones like Hogarth, Fragonard, Delacroix. And then Picasso, De Kooning….The list is long. She loves paintings teeming with activity and with narrative, usually of a moral nature. For her, multiple entry points invite the viewer to discover, to stay with a piece for a while. I imagine her as the A+ student, rooted in history, studying these artists. She will sketch different segments of masterpieces, internalizing them, to the point that she can innately reconstruct the paintings. As a puzzle. Then she will take a little from here, a little from there, and add her own imagination to construct her work. She will reuse her art historical references over and over, never tiring of them. Maybe it’s this minute preparation and dedication which impart her art with its spontaneous, vibrant quality.

Girl on a Swing, 2004, 96 in X 76 in

I love Girl with a Swing, an earlier painting inspired by Fragonard and Goya. The elegant Madame, in an improbable position with her upturned petticoat offered for her lover’s enjoyment, while her dutiful husband does the work. Cecily has struck all the right notes here in terms of color, light, and line. Plus it’s playful, not so sexually overt as some of her pieces.

Carnivaland Lent, 2006 –2008, 97 inX 103 in

Or Carnival and Lent, a tilt to Bruegel. With beautiful color and texture, and full of activity, it is embedded with allusions to sin and excess.

Photography and current events also have their place. The monumental tryptique Where, When, How Often and with Whom? references a Muslim woman recently forced off the beach in Nice. Her attire is morally incorrect in secular France. She is besieged by police, all men, and surrounded by people, mainly white. No one cares. She is all alone.

Where, When, How Often and with Whom?, 2017, triptych, oil on linen, overall 7' 5 3⁄8“ × 33' 7⁄8”

I’m not the only one to enjoy her work. She has become a blockbuster, selling in the millions of dollars. While not a fan of art for the mega-rich, I am a fan of her.

So is this the new Romanticism ? Not in terms of a silver lining, but the luxuriousness of her paintings is a site for sore eyes.

Feeling unexpectedly at home

A myriad of stunning, separate glass pieces brought together in this monumental installation

Chihuly Orange Hornet Chandelier, 1993. Photo: https://www.chihuly.com/exhibitions/colorado-springs-fine-arts-center/chihuly-colorado-springs

It’s a beautiful early fall day in Colorado Springs with the aspens starting to glow and the red formations of the Garden of the Gods to explore. So why go inside, into a museum, most of all one we had never heard of before. As with all that is unexpected, this discovery amazed us. The Fine Arts Center at Colorado College not only has a wonderful collection of American and Spanish Colonial art, but its approach is completely experiential. Everything is done for you to interact with the objects, to be amazed. And to feel at home.

I couldn’t find the artist on the worn label.

Luis Jimenez, Fiesta Jarabe

Sculptures on the front lawn are inviting and set the mood.

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer, 1889-90

Going down a hallway, I looked up to find a moody Sargent portrait at the very top of a long flight of stairs. It reminded me of a red carpet reception, but one in which you needed real determination to arrive at. And the climb was worth it. A daughter of one of the city’s founders, she appears fragile, ghostly, yet with all of the grace that Sargent was masterly at.

From Georgia O’Keeffe to Diebenkorn to Marisol and Surls, we relished the American art.

Marisol, John Wayne, 1963

Richard Diebenkorn, Urbana #4, 1953

James Surls, It’s not about the Numbers, 2002

Georgia O’Keeffe, Dark Iris No. 1

1927

And then the interactivity is what really grabbed us. There is a tactile gallery with it seemed around 100 objects to touch, a Navajo loom to operate. Lithograph stones and etching plates helped me to understand those complicated processes a little better. But most of all, the whole notion of security was flipped upside down. Instead of discipline, the security person was trained in interpretation. As most people only spend 30 seconds in front of art, his aim was to extend that, not to say “don’t touch.” Austin was very skilled, stimulating more observation, and we talked about our conversation with him all the way home.

All photos my own except for Chihuly.

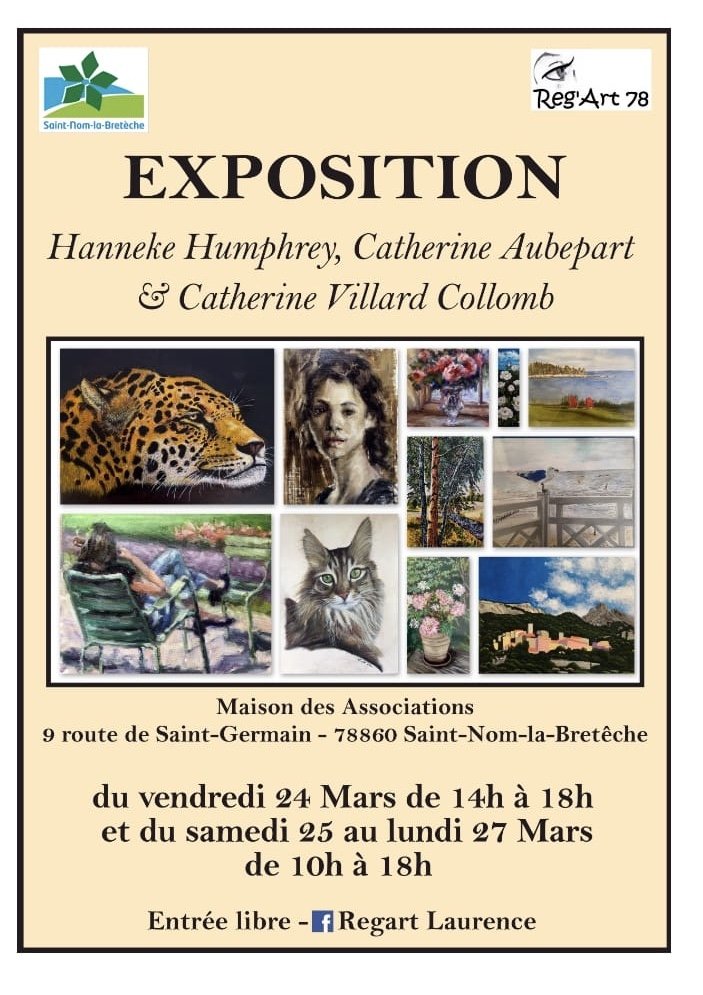

Published Article ---- Spotlight on Local Artists

For full article:

Houston Magazine, Issue 9 https://issuu.com/johnbernhard/docs/arthouston_issue9

The Lake in the Bois de Boulogne, c 1879

The fervor to paint—Berthe Morisot

The energy emanating from Berthe Morisot’s paintings hits me like a lightening rod. Surrounded by so much of her work at the Orsay exhibition, I feel engulfed by the vibrant strokes and colors, as if carpe diem were her motto, unsure that she would have time to capture everything she wanted to—the instant, the emotion.

I take in swaths of canvas that she left bare, work that intentionally looks unfinished and borders on abstraction. Yet while I can imagine her rebellious nature, attacking the canvas feverishly, her style remains both delicate and graceful. Her art is filtered, not a blatant protest.

Never before have I had the opportunity to experience so much of Morisot’s work. If lucky, I have seen one or two of her pieces in museums, yet she was a trailblazer in so many ways. Refusing to follow the dictates of society, she pursued a career, she innovated, but as with many women artists, she has had few retrospectives. So it is a real treat to observe the breadth of her work, which was cut off by her early death at 54.

In her formative years, she studied under Corot and became very close to Manet, two artists whom I love. Paintings like ”The Butterflies” and “Woman and Children on the Lawn” show these influences, with the refinement of Corot’s landscapes and the figures in black favored by Manet.

Woman and Children on the Lawn, 1874

The Butterflies, 1874

But then, look at “In the Wheat”. What a transformation a year later, as she lightened her palette and energized her paint application with the boy immersed in the bright fields. This impressionistic scene contrasts traditional and modern life as we see smoke emanating from factories in the background. Up close, we see how she moved breathlessly, letting the canvas shine through, yielding near abstraction in the foreground.

In the wheat, 1875

Closeup of In the Wheat

The Cradle, 1872

Her preferred subject was the female figure, using family and friends as her models. « The Cradle » is an iconic early piece featured in the first Impressionist exhibition, depicting her sister who abandoned her artistic career for marriage. The composition with its diagonals and contrasting values draws us into the intimate, tender scene.

Young Woman close to a Window, 1879

Such as a magnet, the « Young Woman Close to a Window » takes me into the model’s soul. Why is she indoors when she could be enjoying the summer roses? What is she thinking? Is she expectant? Restless? So many of the women seem so stylish, privileged, but dispirited. While Morisot had broken out from the status quo, her models seem resigned and idle.

When I focus on different parts of the composition, they are like mini-abstractions. Each quadrant is a feast for the eyes. The elegant dress is textured through scratching with the brush handle, and a few lively lines suggest layers of opulent fabric. I can’t help think that a later artist like Joan Mitchell found inspiration in her confident, bold brushstrokes, contrasted thin and impasto paint, and mastery of color.

Child With a Red Apron, 1886

“Child with a Red Apron” shows a similar spontaneity. The scene with the impish little girl looks like an unfinished study, with bare canvas peeking through, sketched forms, and a limited palette. Cool greys and blues dominate, but the warm red of the apron captures the eye. Morisot deliberately left swaths of the canvas unpainted, focusing on what for her was essential, the moment. Again, that instant was indoors, in front of a window.

Isabelle in the Garden, 1885

I was struck by the imploring gaze and minimalism of “Isabelle in the Garden”. The unpainted canvas dominates, and a few dashes suggest a dog in the lap of this young woman who is surrounded by nearly indecipherable flowers. Aspects feel oriental to me, with apricot and green colors as well as calligraphic lines.

Up close, the face is startling with red ears and green lines passing over, yet it all mixes perfectly at a distance.

Close up of Isabelle in the Garden

Mlle Julie Manet, 1894

Then, there is “Mlle Julie Manet. ». So different. A late work painted a year before Morisot’s own death, it shows her daughter mournful after the passing of her father. Morisot seems to have subjugated her dynamic style in favor of mood. She has softened her strokes, blended the paint, more in the manner of her early work, and she has eliminated any representational setting. All I see is the languid, wistful expression of Julie. The green of her eyes is matched in the background and shadows, and the whole is set off by her red hair.

We know that Berthe Morisot forged her career in a world normally blocked to women. Although her notoriety faded after her death, she was successful in life through a combination of luck, talent, and determination. She was fortunate in coming from a wealthy family that supported her ambition to be an artist, at a time when she could not enter the fine arts schools. She was also either fortunate or strategic in choosing a husband who had means and stopped his painting career in order to support hers. Eugene Manet, Edouard’s brother, had been a painter himself. But both talented and determined, she mastered all aspects of painting, and her delicacy, spontaneity, and light palette were innovative.

Self-Portrait, 1885

However, I rarely saw that pioneering aspect in the subjects of her paintings. The women and girls often appear as lovely adornments, straight out of the bourgeoisie, compliant in cloistered lives. Except in her own self-portrait, in which we see an uncompromisingly realistic depiction of Morisot... at work.

All photos my own.

The Language of Art

“Art is the most effective mode of communication that exists.” For me, John Dewey meant that artists often communicate a narrative or a feeling through their work, which we in turn connect with in so many ways. For many of us, being moved by a work of art can have a transformative effect.

Edgar Degas, Russian Dancers, 1899, Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Photo H Humphrey

As a docent, I am mindful of that very personal experience that visitors have. Silence is normal and necessary. At the same time, art can be a way to bring people together, spark a conversation, and further the visitors’ understanding. Rather than delivering a speech, I feel that encouraging people to discover new meanings through discussion leads to a more fulfilling experience. A more memorable one.

That process is neither random nor easy, but stems from a structured, enquiry-based approach. Yet we can be hesitant about talking about art for multiple reasons. We might be more comfortable receiving information than sharing it, or we might lack the confidence of an art history major. Whatever the reason, breaking the ice and stimulating conversation can be a challenge.

John Singer Sargent, Val D’Aosta: Stepping Stones, c 1907, Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Photo H Humphrey

With this in mind, we organized a training session at the MFA Houston led by Al Mock, a friend and docent. He thoughtfully chose these 4 pieces to demonstrate the Language of Art. They’re so different, and yet so alike. When you look at them, what would you like to talk about?

August’s Rodin, Crouching Woman (Cast # 5), 1882, Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Photo courtesy of MFAH

Some of you might say “What’s the story?” Sure, the art history and narrative can be fascinating, but chances are conversation will be scant by starting with that. I can just imagine my kids rolling their eyes and looking for the closest cafe as the lecture starts.

Louis Finson, The Four Elements, 1611, Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Photo H Humphrey

Al suggested a different approach that I embrace, starting with what people notice about each piece. The lines, shapes, colors, textures, and objects we see are palpable. They are easy concepts to get our hands around and talk about. After that, the patterns, composition, and all the design components can come into play. Finally, the icing on the cake might be the story that the visitors unfold by themselves. Well, perhaps with a little prodding. Through this approach, I’d bet that they would go home satisfied with the experience and discoveries.

Edouard Manet, Les Hirondelles, 1873

Counterpoint

Manet, Un Coin du Jardin de Bellevue, 1880

While less peaceful than the museum I wrote about last, the Musée Maillol is another treasure. It’s just the right size, not too overwhelming, in the very tony 7th arrondissement. The permanent collection of the Banyuls master is rich, but we had come for the Bührle Collection. There is something for everyone who loves modern art, which is probably why it was less peaceful. The curators have delightfully highlighted the evolution of many artists, amazing us at every turn.

For example, there’s a signature Manet showing his mastery of black, with the dark and light figures in the foreground catching our attention. A modern painting that is like a bridge between Realism and Impressionism. And then another landscape explodes with free and delicate brushwork, color, and atmosphere. Impressionistic, this intimate garden scene seems more like a Berthe Morisot than a Manet to me. And they did influence each other. They were close, had a complicated relationship, and were even related as she married his brother.

Strolling through the galleries, these surprises reminded me of counterpoint. Iconic styles of artists are mixed with the unexpected, and the whole is just lovely. Buhrle was a brilliant composer, with a gift of uncovering the rare pearl to tell an artist’s story.

Then there is Degas whom we imagine meticulously studying his figures, focusing on movement, and painting inside his Paris studio. Nothing left to chance. We do indeed see the poetic ballet dancers stretched in a contemporary way on an elongated canvas. That gorgeous light and vibrant oranges against blues are stunning. But there is also one apparently plein air painting that seems so unlike him. One in which I get to see a bit of his process. It looks unfinished with his initial mark making present, yet it is not one of his late, ébauche-like pieces. Maybe he did think of it as experimental because he kept it in his studio, never selling it. But then, he did that a lot.

Edgar Degas, Danseuses au foyer, 1889

Edgar Degas, Ludovic Lepic et ses filles, c 1871

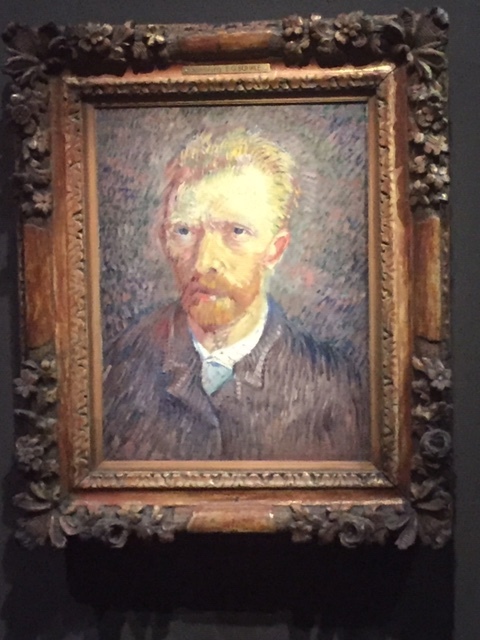

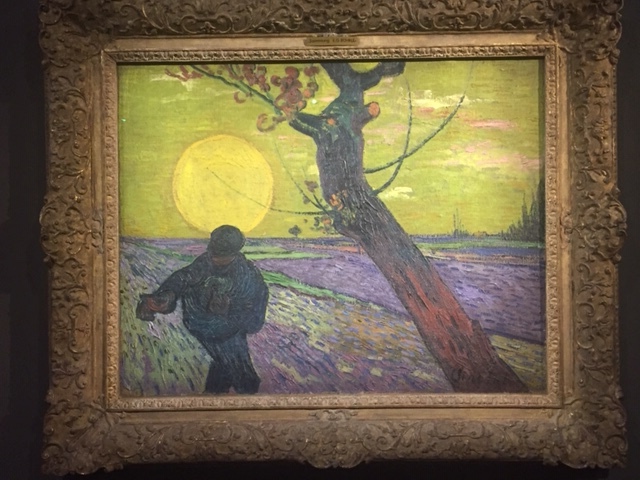

Van Gogh is the star, with a glorious display that shows the artist’s stages succinctly. We see the darker, more naturalistic pieces done in Holland, his Paris period with the influence of Impressionists, and the entrancing “Le Semeur, Soleil Couchant.” How different this farmer is from the one in the first picture. Done in Arles, the complementary colors and dynamic lines are magnetic, and the cropped composition sends me to that brilliant sun. The Japanese influence shows in this and “Branches de Maronnier en Fleur”. Although painted in the last year of his life while he was in Auvers sur Oise, I did not see any trace of his suffering here. The flowers are so gestural, lively, and modern, with the horizontal, close-up composition.

What an overview in these few pieces.

Van Gogh, early pieces done in Holland

Van Gogh, Autoportrait, 1887

Such a contrasting mood from the other done in the Paris period.

Van Gogh, Les Ponts d’Asnieres, 1887. An impressionistic scene of the outskirts of Paris.

Vincent Van Gogh, Le Semeur, Soleil Couchant, 1888

Van Gogh, Branches de Marronier en fleur, 1890

Despite the breadth of this exhibition, there’s a controversial side of Emil Bührle and his art purchases during WWII, which the exhibition addresses. I’m happy just to talk about the aesthetic though!

All photos my own.

PORTRAIT DE SARAH BERNHARDT, GEORGES CLAIRIN, 1876

Rediscovering the Petit Palais, Paris

Rediscovering the Petit Palais, Paris

Read MoreWhat is Art?

Damien Hirst, End Game, 2000-2004 Museum of Fine Arts Houston

It always surprises me how enthused kids under 10 are with abstraction and contemporary art. They are usually more excited about it than my family or some friends. It’s all about the creativity they see, the visual or physical experience they have. And engaging, finding pleasure, maybe even feeling awe certainly seem like qualifiers of whether something is art or not. This always happens when we walk through the Turrell tunnel. Students are mesmerized, feel dizzy, love the changing colors, wonder how it’s made. The same is true for Calder’s mobile gliding above and the calm that it procures.

Installation view with Alexander Calder, International Mobile, 1938 Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Yet sometimes, students will take me to an uncomfortable area. Skepticism. Rejection. They might say “I could do this” or “this is ugly,” and such comments are tough to deal with. So recently I helped put together a training session at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston with fellow docent, Eric Timmreck. He tackled this thought-provoking, even brain-racking subject .

One takeaway from our training is that there just isn’t a magical answer. Simple dialogue can go a long way. Being non-judgmental, acknowledging differing points of view, offering the artist’s intent, and giving historical context can be positive. But that might not always be enough. People can continue to scratch their heads.

Think of how Du Champ teased us with his ready-mades, his urinal titled “Fountain”. Or how Warhol provoked us with his Brillo Box that is literally the product packaging itself. Rauschenberg with his found objects. Hirst with his cadavers and skulls.

What makes all this art? You can’t always grab onto conventional notions like beauty, harmonious color, composition, and shapes. So what else is there? Eric talked about lenses like experience, process, narrative, dialectic, meaning, and truth that can help to understand them. And maybe appreciate them.

Hirst’s “End Game” is an example of this. I have always swooshed my student tours past because of its morbidity. I’d like the conversation to be about livelier subjects, life not death. Yet the children are reluctant to march on. They are drawn like magnets to this piece, making me think their connections may not be the same as mine. So perhaps I could engage with them on different levels after all. What surprises them, what materials are used, what is going on, the different objects they see. We know that Hirst is speaking to mortality, vanitas, and medecine. Maybe those meanings can be discussed, but maybe we’ll already have discussed enough!

This blurb hardly gives justice to what we learnt with Eric, which has allowed me to see a piece of art in a whole new light.

All photos my own

Copyright © 2019 Hanneke Humphrey, All rights reserved.

Discovering Social Sculpture

Project Row House

I have wondered why Project Row House is not rated as one of the top places to see in the city. It is pioneering. Its founder Rick Lowe was even awarded a MacArthur Genius Award. It’s an easy and short drive from Montrose and Midtown. Well, maybe that drive is the answer.

The Third Ward was once the epicenter of the blues scene and a vibrant community. But then it spiraled down for reasons that could merit another post. Driving around, I see remnants of its former glory with stately homes, but am struck by the number of boarded up buildings and a general lack of activity. In fact, I mainly know the area for its shortcuts to get to Eado, which avoid the dreaded highway. But there’s never been enticement for me to stop.

Then I learnt about Project Row House. And I learnt that even longtime Houstonians I know had never ventured there despite the fact that the project is now 25 years old. So I thought, why not organize a tour there for MFAH docents? The tour led by Imani ended up being astonishing.

The founders were all young artists who wanted to regenerate the neighborhood. They decided that social realism, the vector artists often use to make a statement, was not the best solution. This led them to a whole new concept of combining art exhibitions with community development. Since then, “Social Sculpture” has taken off in places like Dallas and as far off as Athens. And not the Georgia one!

To begin, they purchased and restored 22 rundown shotgun houses that serve as studios for visiting artists as well as venues for art shows. Imani took us to the current one, called Penumbras, Hidden Geometries.

One of the Row House installments:

There could be different reasons for focusing on shotgun houses, the first being their prevalence in the South and association with African American culture. John T Biggers, the renowned artist and professor at nearby Texas Southern University, often depicted them in his art.

I found out that shotgun houses likely came from Africa and spread because they are cheap to build and offer some ventilation in the baking heat. Hence the name: you can literally point a gun from the front to the back door.

What is most astounding to me at Project Row House is the community effort. I’m not sure the project will be able to stand up to Houston’s developers and to gentrification. It is so close to downtown and may see a similar fate to that of the Fifth Ward. But the project has created a residential program to help young mothers, a day care center, low income housing, and a small business incubator. The food coop even offers an affordable medical plan.

Project Row House has certainly given me reasons to go back, learn more about Houston’s past and present.

Photos by Eva Maria Campo and myself.

Copyright © 2019 Hanneke Humphrey, All rights reserved.

Exploring Place and Process Jack Whitten

MFAH has three great exhibitions right now that are coming to a close. There is the blockbuster, showcasing the beloved and tragic Van Gogh. Then, Sally Mann with her mysterious photographs of the South, that evoke her home, heritage, and family. And the artist who has touched a chord with me is the most discreet, getting the least attention. He’s Jack Whitten.

I like underdogs. Explorers. And he certainly was one, as an African American growing up in Alabama, in American Apartheid as he called it. Through brilliance and grit, he broke away from the South and headed North. Not an easy feat in 1960. In NYC, he was the first black student at Cooper Union and at the same time melted into the bohemian art scene with the greats like De Kooning and Lawrence. He had discovered a new world and never moved back to the South. His journey even took him as far away as Crete, where he eventually spent his summers sculpting work we see here.

Walking through the exhibition, I am travelling to places not far away, to the harsh reality of the segregated South. But I’m also going to distant places, to traditions from Africa. He had said that his Jug Heads could protect a black person in a society that didn’t, and this tradition likely came from the enslaved peoples of Congo.

Installation view. Jack Whitten, Jug Head I and Jug Head II, 1965, black stained American elm with black shoe polish patina photograph by Hanneke Humphrey. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Embedded in elegant pieces, you will find a myriad of found objects that reference Nkissi power figures. But you’ll also be in the calm, azur waters of the Mediterranean, with the Greek gods Apollo and Dionysus, fishing off the coast of Crete. What all do you see in this one?

Jack Whitten, Homage to the Kri-Kri, 1985, black mulberry, nails, and mixed media. ©Jack Whitten Estate. Courtesy of the Jack Whitten Estate and Hauser & Wirth, and Museum of Fine Arts Houston

The discovery continues for me, with processes that he invented. He broke away from abstract expressionism, so emotionally heavy for him with the Civil Rights movement and the Vietnam War going on. Searching a new path, he started a lifelong focus on materiality. “Slab” paintings, sometimes called Richteresque, came out of that. But Whitten had invented the process earlier…. perhaps we should say Whittenesque.

Jack Whitten, Delta Group II, 1975 Photograph by Hanneke Humphrey. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston

His experimentations with acrylics were pioneering too. He would mold paint like plastic, make films out of it, freeze and then shatter it, and make tiles. From that came a series of abstract portraits that he called Monoliths, which are tributes to important African Americans. They pixelate with color and texture. Always interested in process and craft, he called these “Painting as Collage”.

Jack Whitten, Black Monolith VII (Du Bois Legacy: For W.E. Burghardt, 2014, acrylic on canvas, Private Collection; ©Jack Whitten Estate. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston

I walk through this exhibition in awe of such beauty, such breadth of work, but also of this man whom I would have loved to have known. His seemingly insatiable curiosity, his sensitivity, the intimacy of his work. He kept most of these pieces at home, not showing them to the public until late. The guardian figures, reliquary pieces, and totems must all have had special meanings for him, as they do for me now.

So why does his work seem to get the least attention? He was an engaging personality when you watch videos. The work is multi-layered and wonderful. I think the reason lies elsewhere. Maybe it’s exactly what I like about him, his outsider side.

Copyright © 2019 Hanneke Humphrey, All rights reserved.